©Rizky/BAL

This article was originally written and published in bahasa Indonesia on 2 December 2021.

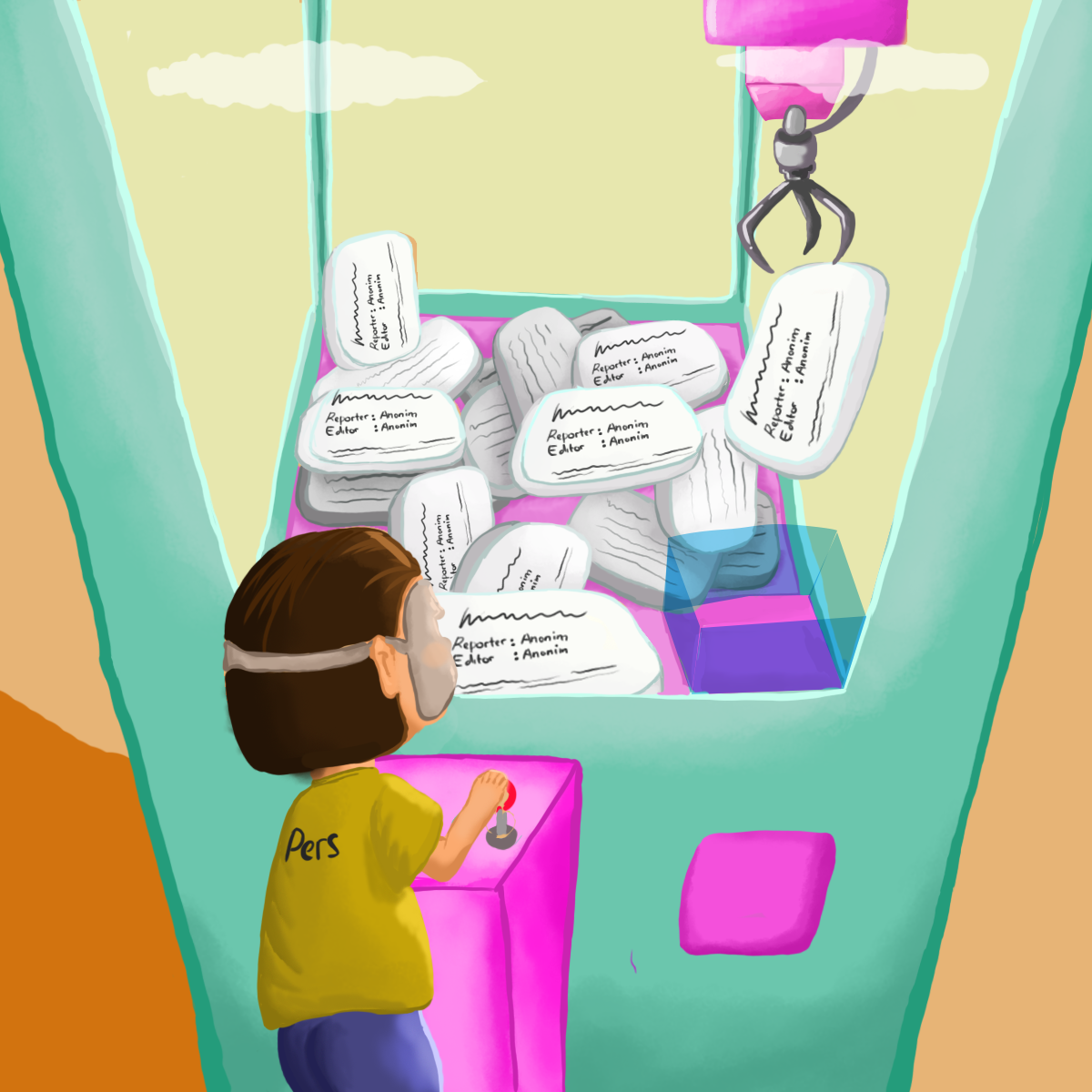

An informant is a vital material for constructing a journalistic product. The validity of the information provided belongs to the news provider and the source. However, we cannot deny there is a possibility that misinformation is a scourge for the masses.

Anonymity is a familiar term in processing a news source. “Anonymity” comes from the Greek word ano-nymia, “without a name”. This term identifies unnamed objects, both human and nonhuman objects (Chawki, 2009: 1). In the context of news sources, anonymity occurs because the informant does not refer to themself as a particular person (Saptiawan, 2018). In this way, anonymity can be interpreted as the action of the press to conceal the informant’s identity. The press will keep it secret until the source reveals themself or there is an intentional dissemination of wrong information (Harsono, 2010). The availability of the anonymous status option is also accompanied by the reporter’s privilege to refuse revealing the source’s identity both to the public and the law. The reporter’s privilege protects the press from external intervention, such as the government (Belsey & Chadwick, 1992). The reporter’s privilege in Indonesia is regulated in the Press Law no. 40 of 1999. It adheres to the Guidelines for the Implementation of the Press Council’s Right to Reject Number 01/P-DP/V/2007.

One of the media that permits the usage of anonymous sources is TEMPO (Setiawan, 2014). In this case, TEMPO allows sources in cases of sexual crimes and children to use the unspecified status. It aims to protect the source’s safety without losing the guarantee of public trust towards the quality of the news. According to Setiawan (2014), anonymity is only given for investigative journalism and must contain a tremendous public interest. Anonymous status is granted to disclose facts and protect the vulnerable source. It means to protect the source from things that endanger their lives, the safety of their families, and the access to new jobs if they are terminated from the job (Harsono, 2010).

An example of using an anonymous source to provide important information is the Watergate scandal that involved Deep Throat. Deep Throat was a pseudonym for the secret informant in the Watergate scandal from 1972 to 1974. The person behind the pseudonym is William Mark Felt, a director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 1971 to 1973. The Watergate scandal was sabotage carried out by Richard Nixon, the 37th President of the United States of America, against the Democratic Party of the United States to win the general election. Deep Throat’s role in the Watergate scandal was to broadcast the sabotage Nixon had done. It caused Nixon to resign from the government. The usage of Deep Throat’s status in the Watergate scandal is proof that providing anonymity to key informants can offer benefits in terms of informant security and favor of the wider community. In addition, the spread of this scandal has triggered an increase in US civil skepticism towards the government.

As Deep Throat’s true identity was still unknown until 2005, many began to speculate about who was behind the leaking of the Watergate scandal. In Felt’s 1979 memoir The FBI Pyramid, he initially denied allegations of Deep Throat status. Despite many suspicions directed at Felt, Deep Throat’s true identity was officially known only to Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein as news writers and Ben Bradlee as editor of The Washington Post. Eventually, on May 31, 2005, accompanied by several parties, such as his daughter Joan Felt and lawyer John D. O’Connor, Felt decided to reveal his Deep Throat identity to the public (Woodward, 2006). The admission was published in Vanity Fair Magazine and republished on the website with the headline “I’m The Guy They Called Deep Throat”, which Woodward and Bernstein later confirmed through The Post.

Andreas Harsono denies the usefulness of using anonymity in the Watergate case in Agama Saya Adalah Jurnalisme (2010). According to him, anonymous sources are less credible, especially when told by intelligence agents, as they must have a certain tendency to spread group interests. The stakeholder often misuses the disguise of an anonymous source to divide the public into several camps because of particular intentions. One of the harmful impacts of anonymity in journalism is the case of the murder of Jamal Khashoggi in 2018.

Jamal Khashoggi was a prominent Saudi journalist who was quite vocal in criticising policies in his home country, especially the policies of Mohammed bin Salman. Even Khashoggi used to be close to the government. After exiling himself to the United States, he intensified his criticism of Prince Mohammed’s policies through Twitter and The Washington Post. The objection then turned into speculation about the cause of his death. Anonymous sources said that Turkish police believed Khashoggi was killed in the consulate when he was asking for divorce papers. There were also allegations that before Khashoggi was declared missing, Prince Khalid bin Salman, the Saudi ambassador to the United States, had reassured him that it was safe to visit the consulate. With this information, the CIA concluded that the murder of this senior journalist involved Khalid bin Salman, Saudi’s ambassador for the United States. After the CIA conclusion was circulated, the Saudi royal family, including Prince Khalid, denied the news from an anonymous source with questionable credibility. The Saudi Arabian government eventually admitted that Khashoggi’s death was in the consulate building, though they still deny that Prince Khalid took part.

From the murder of Khashoggi, the presence of an anonymous source in a case may intervene in the investigation and provide uncertain testimony. The situation will become even more complicated if the information is being spread in the news because journalists or the press as information media is the fourth pillar of democracy that goes hand in hand with law enforcement to create a balance in a country (Mada, 2014). The Washington Post’s role, in this case, is to provide information based on people who are familiar with the matter and refer to the CIA’s conclusions from anonymous sources. Unidentified resources’ viewpoints have distorted the CIA’s decision-making on the Khashoggi case.

Although there are pros and cons to using anonymous sources, there are seven undeniable conditions in obtaining the anonymous status by Kovach and Rosenstiel in Warp Speed: America in the Age of Mixed Media (1999, as quoted in Harsono, 2010). The first condition is that the informant has direct involvement in the events covered by journalists. It means that a resource person is a person who directly witnessed the incident. Second, the safety of the informants is threatened if their identities are revealed. By closing the identity of the informant, their well-being remained intact. Third, informants have a clear public interest. In this case, journalists must know the reasons behind the disclosed information. Fourth, resource persons have good integrity. Fifth, the anonymous status given must obtain the editor’s permission. Sixth, the number of anonymous sources in the news is not less than two due to the verification from one source to another. Seventh, the press will revoke the granted anonymous status if the source provides misleading information intentionally. Thus the press will disclose the source’s identity to the public.

The permission to use anonymous sources depends on each press institute, considering that the press’ credibility will be affected by the anonymous status of the sources. The public shall process anonymous sources with skepticism. Skepticism towards the usage of anonymous sources will lead the reader to the following question: What is the tendency of the sources in conveying the information? As readers, we must attentively examine the news. Furthermore, the bias of the media itself needs to be concerned. Good cooperation between the press and the public is required to disseminate correct and valuable news.

Authors: Aniq Hanani Maimanah dan Tuffahati Athallah (Intern)

Editor: Mayasari Diana

Illustrator: Rizky Aisyah (Intern)

Translator: Tuffahati Athallah

References

BBC. “Jamal Khashoggi: Turkey Says Journalist Was Murdered in Saudi Consulate”. October 07, 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-45775819. Accessed on 17 January 2022.

BBC. “Jamal Khashoggi: US Says Saudi Prince Approved Khashoggi Killing”. February 26, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-56213528. Accessed on 17 January 2022.

Belsey, A., and R. Chadwick. Ethical Issues in Journalism and the Media. London & New York: Routledge, 1992.

Branigin, William, and Von Drehle, D. “Washington Post Confirms Felt Was Deep Throat”. The Washington Post, May 31, 2005. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/technology/2005/05/31/washington-post-confirms-felt-was-deep-throat/8d13cc72-6e02-422a-b3a8-76631aa9b904/. Accessed on 16 January 2022.

Chawki, M. “Anonymity in Cyberspace: Finding the Balance between Privacy and Security”. International Journal of Technology Transfer and Commercialisation 9, no. 3 (2009): 183-199. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijttc.2010.030209.

Coskun, Orhan. “Exclusive: Turkish Police Believe Saudi Journalist Khashoggi Was Killed in Consulate – Sources”. Reuters, October 06, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-politics-dissident/exclusive-turkish-police-believe-saudi-journalist-khashoggi-was-killed-in-consulate-sources-idUSKCN1MG0HU. Accessed on 17 January 2022.

Harris, Shane, Greg Miller and Josh Dawsey. “CIA Concludes Saudi Crown Prince Ordered Jamal Khashoggi’s Assassination”. The Washington Post, November 16, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/cia-concludes-saudi-crown-prince-ordered-jamal-khashoggis-assassination/2018/11/16/98c89fe6-e9b2-11e8-a939-9469f1166f9d_story.html. Accessed on 17 January 2022.

Harsono, Andreas. Agama Saya Adalah Jurnalisme. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Penerbit Kanisius, 2010.

Mada, Gading Tian. “Penyembunyian Identitas Pelaku Tindak Pidana Oleh Insan Pers Menurut Kuhp Dan UU Nomor 40 Tahun 1999 Tentang Pers.” Mimbar Keadilan, Jurnal Ilmu Hukum Edisi Januari-Juni, (2014): 109-126. ISSN: 0853-8964.

O’Connor, John D.. “I’m the Guy They Called Deep Throat”. Vanity Fair, July, 2005. https://archive.vanityfair.com/article/2005/7/im-the-guy-they-called-deep-throat. Accessed on 16 January 2022.

Saptiawan, Itsna H. (2018). “Dari Anonim Kembali ke Anonim”. SeBaSa: Jurnal Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra Indonesia 1, no. 2, (2018): 80-88. ISSN: 2621-0851.

Setiawan, L. D., and K. Ambardi. “Narasumber Anonim dan Berita (Studi Kasus Kebijakan Redaksional Majalah Tempo mengenai Narasumber Anonim dalam Rubrik Laporan Utama Kasus Korupsi)”. Universitas Gadjah Mada (2014).

Smith, Saphora. “Saudi Arabia Now Admits Khashoggi Killing Was ‘Premeditated”. NBC News, October 25, 2018. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/saudi-arabia-now-admits-khashoggi-killing-was-premeditated-n924286. Accessed on 17 January 2022.

Von Drehle, D.. “FBI’s No. 2 Was ‘Deep Throat’: Mark Felt Ends 30-Year Mystery of The Post’s Watergate Source”. The Washington Post, June 01, 2005. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/fbis-no-2-was-deep-throat-mark-felt-ends-30-year-mystery-of-the-posts-watergate-source/2012/06/04/gJQAwseRIV_story.html. Accessed on 29 November 2021.

Woodward, Bob, and Carl Bernstein. The Secret Man: The Story of Watergate’s Deep Throat. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 0-7432-8715-0.